Accounting for Leases

On January 1, 2019, the new standards on lease accounting came into effect. This is one of the largest changes to accounting rules in decades. As Gord Downie famously said, “It’s been a long time coming…” But was it well worth the wait?

What prompted the change?

Starting in 2019, IFRS and US GAAP require that most leases be reflected on the lessee’s balance sheet. This was a joint convergence project between IFRS and US GAAP that started in 2005 and didn’t finish with convergence (one lease accounting model). If you have ever studied accounting and memorized the tests to distinguish between a capital lease and an operating lease, I know what’s on your mind: you are afraid it’s all been wasted time.

Why would a company lease something?

A company can either buy or rent (lease) an asset. Why would a company choose to rent vs own? There are many reasons but chief among them would be less upfront capital required and flexibility to change with technology. Leasing is common in the airline, retail, and vehicle rental industries. Consider how much it would cost Lululemon to own all of the real estate underpinning all of their store locations.

What was the issue?

Depending on the terms of the lease, some leases were on the balance sheet as a liability (capital or finance lease) and some leases were off balance sheet (operating lease).

Operating leases, therefore were a form of off-balance sheet financing. Financial statements didn’t properly capture the obligation implicit in an operating lease. An operating lease payment represents a contractual commitment similar to principal and interest payments on debt.

Why does it matter?

The previous classification of leases had significant effects on financial metrics. Similar sized companies in similar businesses could have had very different EBITDA margins, Return on Assets/Invested Capital or Debt to Capitalization calculations depending on their mix of capital leases vs operating leases.

In finance, we account for the fact that a company used operating leases by adjusting two things:

- Adding rent expense back to operating income

- Adjusting the debt by either multiplying the lease expense by a multiple OR discounting back the future operating lease payments by the pre-tax cost of debt.

Should I throw out my study notes from my university accounting courses?

Not quite yet. Here is a summary of both accounting rules:

| IFRS 16 | US GAAP |

| · No distinction between a capital and operating lease: a lease is a lease! |

· Still distinguish between a capital lease and operating lease · Although the explicit tests no longer exist, in general, test to see if you are using the asset for most of the asset’s life |

Recall that a capital lease meets one of the following criteria:

- Bargain Purchase Option

- Ownership of the leased asset transfers to the lessee at the end of the lease

- Lease term is greater than 75% of the useful life of the asset

- PV of lease payments is greater than 90% of the FMV of the asset

Let’s run through an example using IFRS and US GAAP…

A company (lessee) enters into a five-year lease with the following lease payments:

The lessee’s incremental borrowing rate is 8%. The lessee’s incremental borrowing rate is defined in IFRS 16 as “the rate of interest that a lessee would have to pay to borrow over a similar term, and with a similar security, the funds necessary to obtain an asset of similar value to the right-of-use asset in a similar economic environment.”

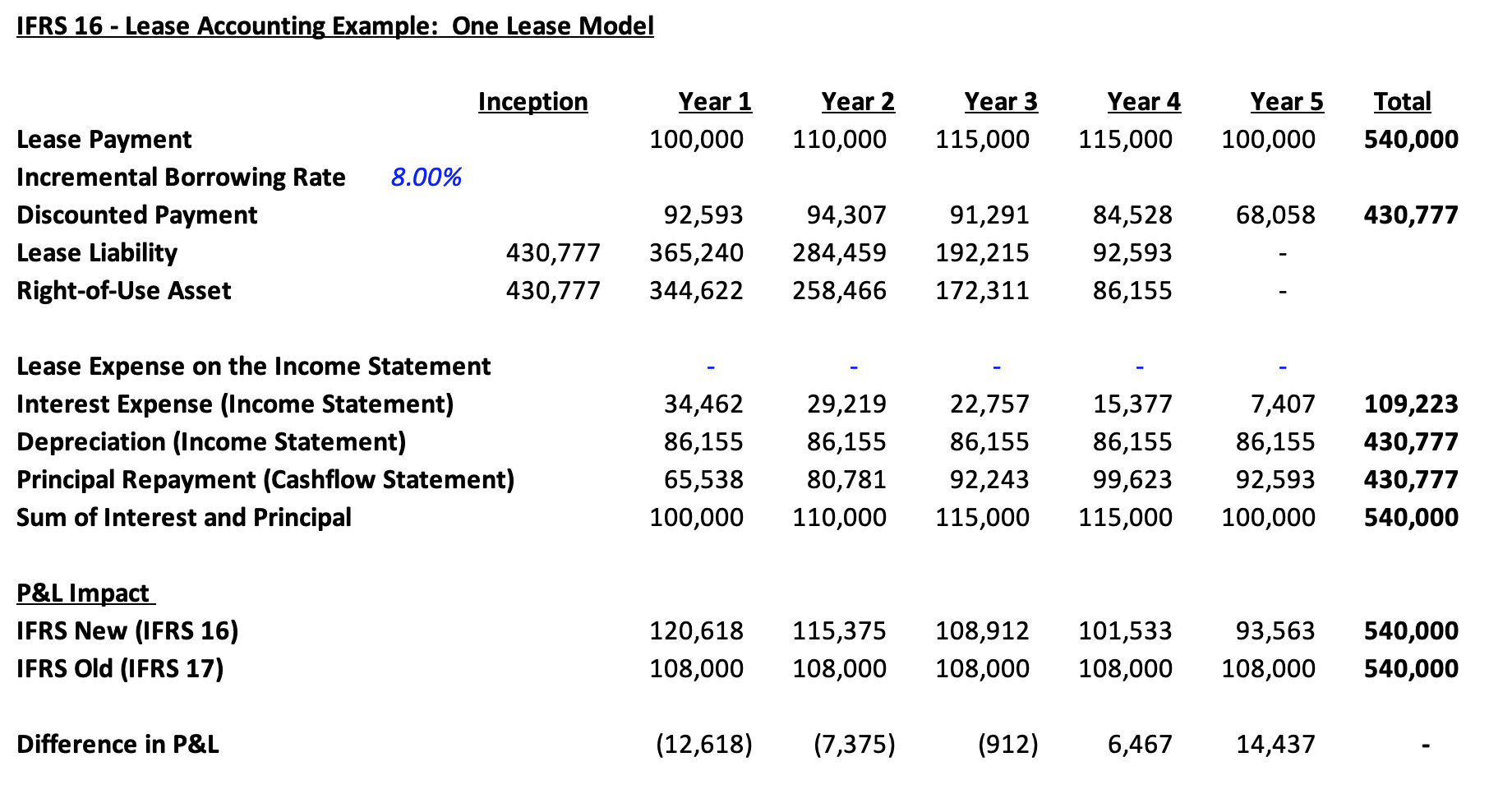

IFRS Example: Accounting for a Lease (Previously an “Operating Lease”)

- Assume a single lease accounting model (i.e. no distinction between a capital/finance lease and an operating lease)

- Discount the lease payments back to the present using either the interest rate used by the lessor OR the lessee’s incremental borrowing rate (in 99% of cases, you would never know the lessor’s rate)

Balance Sheet Impact

The present value of the discounted payments appears on the lessee’s balance sheet as an asset (Right-of-use Asset) and as a liability (Lease Liability).

Income Statement Impact

Use the Incremental Borrowing Rate to calculate Interest Expense. Depreciate the “Right-of-use Asset” over the term of the lease. For our example, we will use straight-line depreciation. Under the former IFRS lease rules (IFRS 17), operating lease expense would have been recognized as an expense on a straight-line basis over the lease term.

Cashflow Statement Impact

Add back depreciation to Cashflow from Operations and deduct the Principal Payments (Lease Payment minus Interest Component) from Cashflow from Financing.

P&L Impact

The total expense hitting the Income Statement over the course of the lease is the same. The only difference is timing.

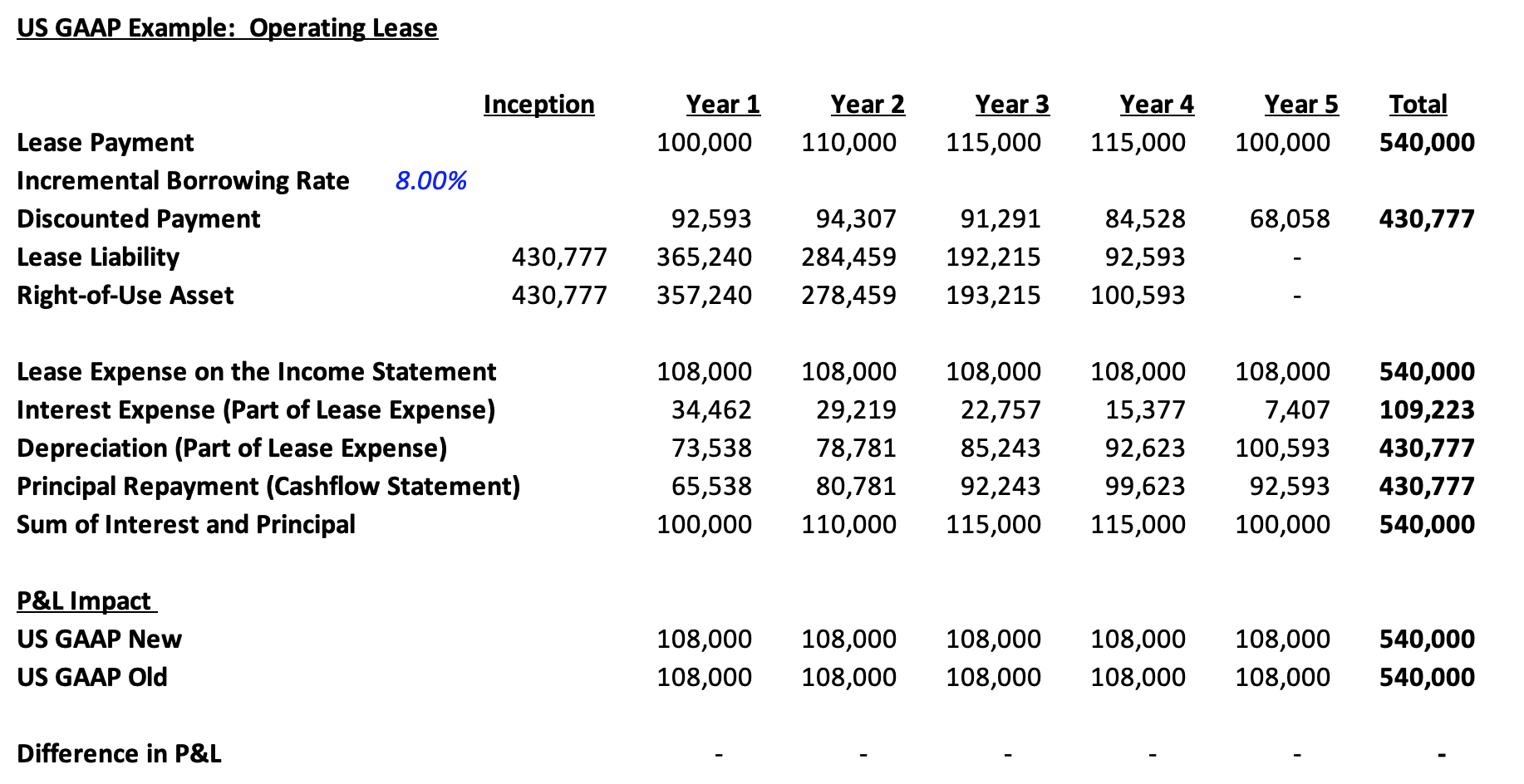

US GAAP Example: Accounting for an Operating Lease

- Distinguish between a capital lease and an operating lease: most leases (both operating and capital leases) will show up on the Balance Sheet as a Right-of-use Asset and a Lease Liability

- For an operating lease, the lease expense is a single line in operating expenses on a straight-line basis (the total lease expense over the term of the lease divided by the number of years). This is unchanged from legacy US GAAP.

- Discount the lease payments back to the present using either the interest rate used by the lessor OR the lessee’s incremental borrowing rate (same method as IFRS)

- The “Right-of-use Asset” is depreciated by a number that is “backed into” by subtracting the calculated interest cost from the straight-line lease expense

Balance Sheet Impact

The present value of the discounted payments appears on the lessee’s balance sheet as an asset (Right-of-use Asset) and as a liability (Lease Liability).

Income Statement Impact

Lease Expense is a single line in operating expenses calculated on a straight-line basis. This is still above EBITDA! Take note that we are solving for depreciation by taking the straight-line lease expense and subtracting the interest component. Also, the depreciation or the right-of-use asset is increasing from the start of the lease to the end of the lease.

Cashflow Statement Impact

The only impact is to Cashflow from Operations. Add back the straight-line lease expense from the income statement and deduct the actual lease expense for the period.

P&L Impact

The total expense hitting the Income Statement over the course of the lease is the same.

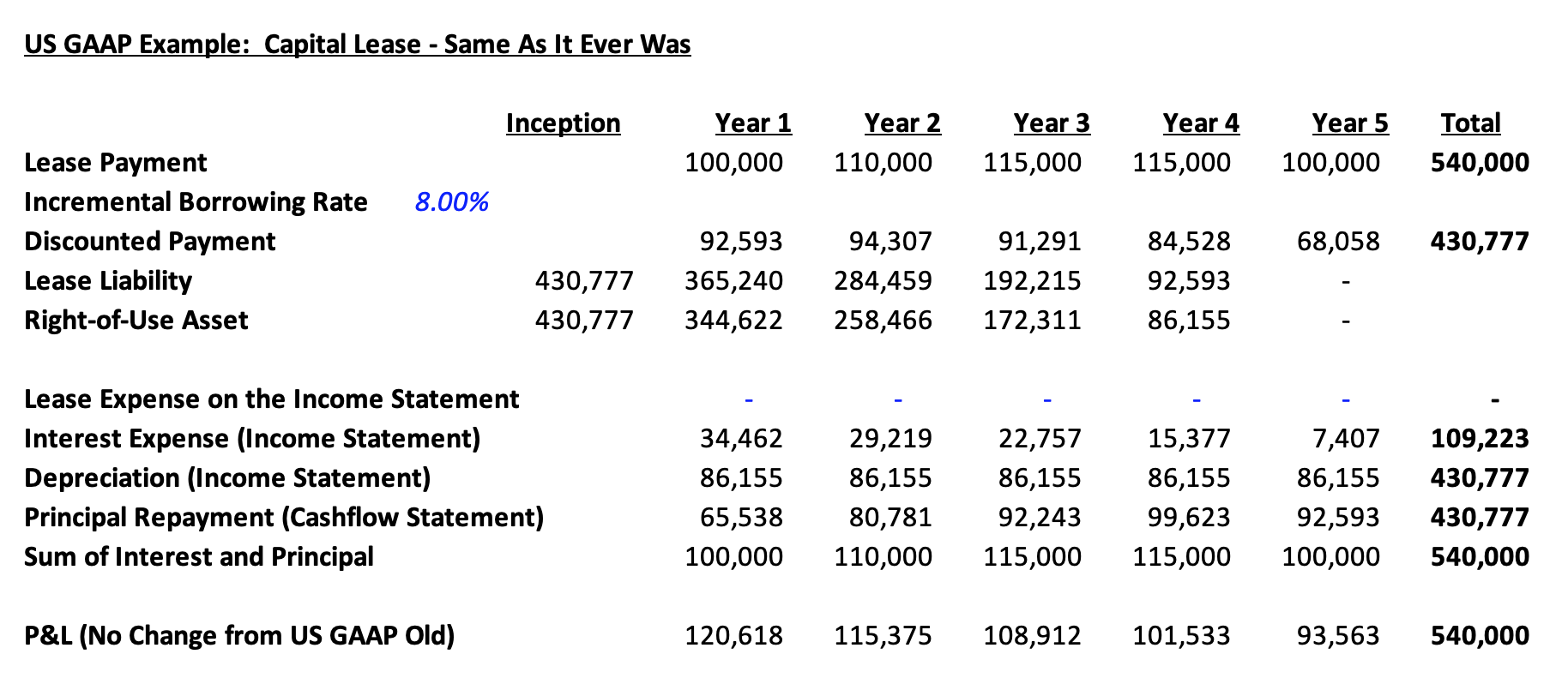

US GAAP Example: Accounting for a Capital Lease

- Distinguish between a capital lease and an operating lease: the leased asset and liability appear on the Balance Sheet as a Right-of-use Asset and a Lease Liability

- Balance Sheet, Income Statement and Cashflow Statement impact has not changed

- Discount the lease payments back to the present using either the interest rate used by the lessor OR the lessee’s incremental borrowing rate (same method as IFRS)

- The “Right-of-use Asset” is depreciated over the lease term

Balance Sheet Impact

The present value of the discounted payments appears on the lessee’s balance sheet as an asset (Right-of-use Asset) and as a liability (Lease Liability).

Income Statement Impact

Use the Incremental Borrowing Rate to calculate Interest Expense. Depreciate the “Right-of-use Asset” over the term of the lease. In this example, use straight-line depreciation.

Cashflow Statement Impact

Add back depreciation to Cashflow from Operations and deduct the Principal Payments (Lease Payment minus Interest Component) from Cashflow from Financing.

Impact on Financial Analysis

EBITDA Margin: If you are comparing EBITDA margin between companies, add back lease expense if one of the companies has operating leases and prepares its financial statements using US GAAP.

Debt to EBITDA: See above. Adjust EBITDA.

Debt to Cap: No adjustments needed.

Year over Year Comparisons: These will be tough! Under IFRS and US GAAP, companies do not need to restate prior years’ Balance Sheets or Income Statements (although they may choose to do so). They can make an adjustment to opening equity for the start of the period where they adopt the new accounting for leases.